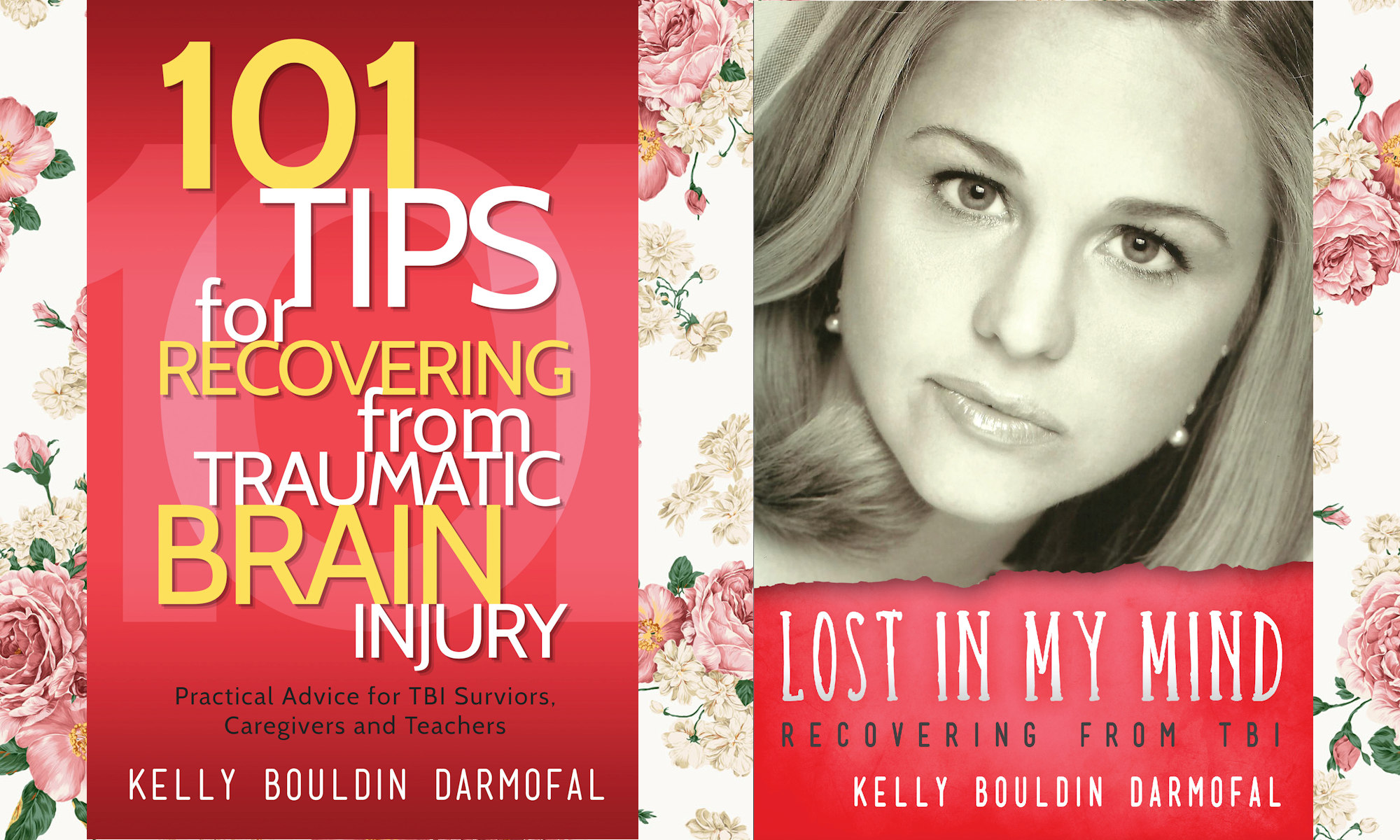

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: But with the publication of Lost in My Mind, I mean, really once you publish your history, there’s no going back from that point. You already know.

Carrie: It sounds like that’s good advice for work and school. We work with people who might have to make choices where they can’t take a job where you have to stand for 12 hours, or you might need to work part-time. So it sounds like that’s good advice outside of school, too.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, yeah, and then when you get into the working world with a TBI, you fall under the ADA regulations with employers. I mean, if you’re already working at a company, and you have a head injury and you can’t stand for as long, they’re required through the ADA to get you a chair.

Carolyn Bouldin: One thing I’d advise anyone who has someone with TBI in their family, read the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA, read the Americans with Disabilities Act or ADA. Because actually, you get a lot of benefits from having a disability. It’s one of the things that my sister provided for me from her library before I had the internet, and it was helpful.

Carrie: Constance is a teacher. And some day, when you’re able to come see us in person, she ran a TBI program in Mesa where the teachers identified, not just the students that had the sports injuries, because we’re doing a good job knowing who has a concussion during football practice. We’re not doing a good job getting those kids that had a car accident on the weekend, fell off their bike on the weekend, and then what happened. So Constance, I know as a fellow teacher, you’ve got a lot to say.

Constance: I’m getting chills, just listening to this. Kudos to you, Kelly, for advocating, because like you said, with anxiety, you want people to know. Kudos to you, Mom, for knowing the educational system, because as a provider of traumatic brain injury services for 23 and a half years, they are the people that made me a better teacher, informing families, the ones that ask questions that had high expectations. I’ll tell you one thing I did tell my students, because some of them were going for employment and jobs.

I would never tell them something they could or couldn’t do. I was always there as a sounding board, but I told them, “It’s up to you what you want to devote.” Now, knowing that I’m going by 23 and a half years, the legal system has come a long way since then. So it’s arranged by hours, but in my head, I don’t want to put them on the register at McDonald’s at lunchtime when there’s a rush. Someone’s going to say something unkind to them, and they’re going to react. So I let them find their niche, and I’m there as a sounding board, but you’re giving me chills hearing both of you talk because of my experience in both areas. So kudos to you, absolute kudos.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Thank you.

Carolyn Bouldin: Can I add one thing? When Kelly was about to graduate from college, we did consult an attorney who dealt with employment issues so she could discern what she did and did not have to tell a potential employer, and that was a wonderful thing. Basically in writing, it could be a little email you’ve hidden somewhere. If you’ve told the employer in writing that you suffered a traumatic brain injury, then you’re in. I mean, they really can’t fire you if you are doing your job well. They might have to move you to another place in the company, but you don’t owe them every detail of your disability, but you have to let them know in writing that you have a disability.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: So basically, what I’ve done is taken a copy of my book and given it to principals where I work, then I’m like, “Boom.” If they choose not to read it, that’s on them. So they know.

Carrie: And sometimes, not disclosing and leaving the room for the proper education can lead to a lot of problems. I’ve seen people, they can do a layoff. There’s a lot of other ways.