Q: Your story sounds very inspiring. I am especially interested because my daughter had a TBI many years ago. One result of that injury which has evaded successful treatment is what I refer to as an intention tremor on her right side. I read that you started using your left hand because of a similar condition.

My daughter is now taking medication for the tremor and has also started botox injections in her arm, and there has been some improvement, but not enough to use her right hand for everyday tasks like eating, drinking, writing, etc.

What treatments or procedures, if any, have you tried for tremor, and how well have they worked for you?

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Higher Education

Cammie: Hello. This Autumn sitting here with me. Autumn had her TBI just 11 months ago, but she’s in college right now, and she struggles with her lack of short-term memory. So she could only take one course at a time. I was curious if you struggled with that when you were doing your school.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yes, yes, without a doubt, yes. And I believe in college, I would take three or four courses.

Carolyn Bouldin: Three, actually but one could be voice or something like that, or art and take one in the summer, in summer sessions. Her first college course was math in the summer.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, it was the summer before I even began college. Basically, I was always taking some kind of school coursework because of that, because two different subjects would just totally get mixed up in my Bermuda Triangle brain. And also, if I could take one course, maybe a math course and then something different, like an English course or a reading course, and then maybe voice or something like that, then there wouldn’t be that much overlap in the type of knowledge that I was having to memorize. So it was easier for me to separate. I’m not sure if they were in different parts of the brain or what. I’m that well-versed on the brain anatomy, but-

Carolyn Bouldin: Kelly tended to sign up for too many classes for eight semesters, and then drop one or two.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yes.

Carolyn Bouldin: That’s the denial part. “Sure, I can handle this, but I can’t really,” but there were things. It’s like knowing what my child knows and what she doesn’t. She remembered Spanish. When she first started talking and the doctor said, “Count to 10,” she went, “Uno, dos, tres,” and it was the janitor who said, “She is counting. She’s counting in Spanish.” She remembered Spanish. It was English that was a little hard, but balancing. A lot of people advised Kelly to take performance classes where you perform, where you act, where you give speeches, but you can have notecards. And your first-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: But my speech is slurred and a bit slower, or it used to be a lot worse. And so, I shied away from that advice for that reason, denial, yes, but my main goal through everything was just I wanted to be normal. I wanted to achieve normalcy again and-

Carolyn Bouldin: And there’s no such thing.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Exactly.

Carolyn Bouldin: There’s no such thing at all.

Cammie: it is a struggle because she’s been told by an instructor at the college, “You won’t be able to do this,” which-

Carolyn Bouldin: Lots of teachers and professors have told Kelly that.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: When I went back to grad school, just so you know, I had an instructor who should remain nameless tell me, “Well, I shouldn’t give her accommodations, because she’s in grad school.” I’m like-

Carolyn Bouldin: It’s like she’s not being blind or something.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, and I’m like, “That’s okay.” I did not have words or kind words for him at that time, but that’s okay. I just had to keep on keeping on. And yes, he did give me modifications, so I won.

Carolyn Bouldin: There was a betting pool among professors about who would win, him or you, and you won, but there’s nothing wrong with taking one class at a time, or a hard and an easy. Using the summers helped to focus on that one class, and the higher you go in college, usually it gets easier, because you’re doing something you love, like signing. I have a first cousin who is a teacher, who works with deaf students and goes to class with them and signs, and it’s a wonderful job.

Q&A: Living and Working with a TBI Disability

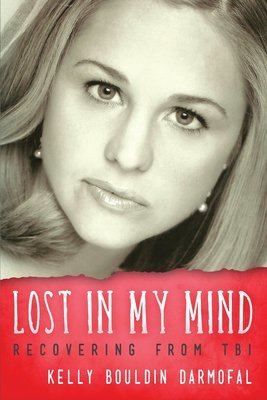

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: But with the publication of Lost in My Mind, I mean, really once you publish your history, there’s no going back from that point. You already know.

Carrie: It sounds like that’s good advice for work and school. We work with people who might have to make choices where they can’t take a job where you have to stand for 12 hours, or you might need to work part-time. So it sounds like that’s good advice outside of school, too.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, yeah, and then when you get into the working world with a TBI, you fall under the ADA regulations with employers. I mean, if you’re already working at a company, and you have a head injury and you can’t stand for as long, they’re required through the ADA to get you a chair.

Carolyn Bouldin: One thing I’d advise anyone who has someone with TBI in their family, read the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA, read the Americans with Disabilities Act or ADA. Because actually, you get a lot of benefits from having a disability. It’s one of the things that my sister provided for me from her library before I had the internet, and it was helpful.

Carrie: Constance is a teacher. And some day, when you’re able to come see us in person, she ran a TBI program in Mesa where the teachers identified, not just the students that had the sports injuries, because we’re doing a good job knowing who has a concussion during football practice. We’re not doing a good job getting those kids that had a car accident on the weekend, fell off their bike on the weekend, and then what happened. So Constance, I know as a fellow teacher, you’ve got a lot to say.

Constance: I’m getting chills, just listening to this. Kudos to you, Kelly, for advocating, because like you said, with anxiety, you want people to know. Kudos to you, Mom, for knowing the educational system, because as a provider of traumatic brain injury services for 23 and a half years, they are the people that made me a better teacher, informing families, the ones that ask questions that had high expectations. I’ll tell you one thing I did tell my students, because some of them were going for employment and jobs.

I would never tell them something they could or couldn’t do. I was always there as a sounding board, but I told them, “It’s up to you what you want to devote.” Now, knowing that I’m going by 23 and a half years, the legal system has come a long way since then. So it’s arranged by hours, but in my head, I don’t want to put them on the register at McDonald’s at lunchtime when there’s a rush. Someone’s going to say something unkind to them, and they’re going to react. So I let them find their niche, and I’m there as a sounding board, but you’re giving me chills hearing both of you talk because of my experience in both areas. So kudos to you, absolute kudos.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Thank you.

Carolyn Bouldin: Can I add one thing? When Kelly was about to graduate from college, we did consult an attorney who dealt with employment issues so she could discern what she did and did not have to tell a potential employer, and that was a wonderful thing. Basically in writing, it could be a little email you’ve hidden somewhere. If you’ve told the employer in writing that you suffered a traumatic brain injury, then you’re in. I mean, they really can’t fire you if you are doing your job well. They might have to move you to another place in the company, but you don’t owe them every detail of your disability, but you have to let them know in writing that you have a disability.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: So basically, what I’ve done is taken a copy of my book and given it to principals where I work, then I’m like, “Boom.” If they choose not to read it, that’s on them. So they know.

Carrie: And sometimes, not disclosing and leaving the room for the proper education can lead to a lot of problems. I’ve seen people, they can do a layoff. There’s a lot of other ways.

Q&A: Going to college with a Traumatic Brain Injury

Carolyn Bouldin: I can tell now from the look on Kelly’s face. When Kelly did her student teaching, she came home and said, “I have to teach a unit on Ancient Rome,” and you looked blank and I knew the problem. I knew the problem. She knew lots about Ancient Rome. She didn’t know what a unit was, and I learned slowly. I could tell where she’s snagged. So as soon as she knew what a unit was, she did beautiful work. Do you remember?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yes.

Carolyn Bouldin: But that happens now. Yes, just common words.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah.

Carolyn Bouldin: Long words are easier to remember, I think.

Carrie: You graduated high school, and what did you set your sights on next?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: I graduated high school, and I wanted to go to college, without question. However, all my friends were going to places in other cities, states, all around, but I knew I had to stay relatively close to home near my doctors at Brenner’s Children’s Hospital. And so, yeah, I looked at Wake Forest and some other schools like that, that would have been way too difficult. And Wake Forest, at that time, could not agree that all of their instructors would abide by my IEP (Individualized Education Plan), which I’m sure things have changed.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: And with my current laws, it would be much better, but Salem College in Winston met with me and my mom, and they did agree that even though they were private and they didn’t legally have to abide by my IEP, they told us that they would. I’m not sure. Did we get that in writing, though?

Carolyn Bouldin: Probably not, probably not in writing.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: So we’ve learned from then you always get everything in writing.

Carolyn Bouldin: We’ve learned to email everything.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yes.

Carolyn Bouldin: Everything a teacher promises you or an administrator-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: You can even do it sneakily like, “Oh, I hope you have a good vacation, blah, blah, blah. By the way, when you said X, Y, and Z, is this what you meant?” And then, they’ll write back and say, “Oh yeah, that’s exactly what I meant, thank you.” And then, if you save that, then you have it.

Carolyn Bouldin: Or texting works too, but keep a record of promises.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah.

Carrie: And that could be for all different kinds of reason. They could have 400 students, or they could see you in class and think you look just fine and that you don’t need that anymore. We work with a lot of students. We hear sometimes from college instructors that a student will tell them at the end of the course, “Well, I’ve had three concussions. I think I’m having a problem.” It sounds like you started out working right with the Student Disability Center, or you started right out talking about how you need help or accommodations.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: I did. Actually, I had a piece of paper that pretty much listed everything I had been through, what my problems were and stuff like that, and what I needed, multiple-choice testing rather than fill in the blank, or at least fill in the blank with word banks to help trigger memories. I would hand that to each one of my teachers the first day of class, because that way they would know without me having to explain it to them, because I was still having a lot more difficulties with expressing my needs, advocating for myself.

I had a lot of difficulty with that. And also, I had a great amount of anxiety, and I still have so much trouble with anxiety, that just to have that piece of paper with me, it took so much anxiety away, because I knew that I could just hand that to them. I wouldn’t even have to tell them what it was, and they could read it and learn pretty much all they needed to know about me as a student, and I didn’t have anxiety.

Carrie: What do you say to a fellow survivor who maybe doesn’t want to disclose that, because they don’t want to be seen as different by their instructor?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Well, yeah, it is hard. People who just experienced a TBI, they don’t want to be seen as different, and I was exactly like that too, but just keeping it real. I mean, if you have had a TBI, people know. People can tell. Oh yeah, thank you, Mom. From 101 Tips, my book, it says, “Number three, tips for TBI survivors, denial can both hurt and help you. However, you must learn to accept your body’s recovery pace.” So basically, you do have to come to terms with what you are able to do and what you’re not able to do.

And from that, you’ll come to a place where you will realize that you’ll have to disclose some things about what your limitations are, because if you don’t, then people will probably think worse about you.

Carolyn Bouldin: I found the denial very difficult. Kelly wanted to drive a car before she should’ve, go places she shouldn’t. I can’t tell you how many things, but-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: But denial can also help you.

Carolyn Bouldin: She pushed herself. She took honors’ classes when she could have taken basic classes, and that helped. You rise to the level of your competition, I do believe, and I think it helped her. So it’s not easy to admit that you’re flawed, but once you can, people are wonderful.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: It took me years.

Carolyn Bouldin: Yes, years.

Q&A: Learning to Learn Again

Carolyn Bouldin: Anyway, I was lucky to be a teacher. I worked with June Horton. I studied Orton-Gillingham phonics and worked with special-needs children. So I could turn those skills to you.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: And then, you had one.

Carolyn Bouldin: And then, I had one, but I still listened to Kelly. I could say, “What helps you remember things?” And she learned to talk, but she took the mirror off the wall in her bedroom, sat in the floor, looked in the mirror and tried to sing rap music to your radio, and she just developed her own strategies.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: To increase clarity and watch my mouth movements, yeah.

Carolyn Bouldin: But she wanted to get well so badly and go back to school that she just figured out her own ways, playing pool, just whatever worked. I know Kelly switched from her right hand to her left hand, because she just couldn’t make that right hand stop shaking, and your doctors didn’t want you to quit, but you just quit.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Well, I mean, there comes a point. You try and try and try. Eventually, you have to stop and just move on, because you have to be able to sign your name when you write checks. And now, that’s not a big issue anymore, but it comes in handy though, because a lot of the students that I work with now suffer with dysgraphia, and they complain and complain about it. “I don’t want to have to write,” and all that stuff, and I’m like, “Hey, I have a bilateral hand impairment. I had to teach myself how to write with the other hand. Can you do that?” And I’m like, “So I feel your pain, but you got to write. Suck it up.”

Carrie: Now, your injury was when you were 15, and you immediately wanted to go back to school and worked hard for that. What was your experience like? Did you go back to school gradually, or how did that-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yes. Well, I don’t remember the exact dates. Was it before Christmas in December?

Carolyn Bouldin: After.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: It was after Christmas. I would go back for an hour at a time, and my mom would drive me, and the administration wanted my mom to stay on site for liability issues, I guess. And so, she would stay in the teachers’ lounge where I would attend. I think it was my Spanish class.

Carolyn Bouldin: Yeah.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, and so I would attend that one class and then go home. And then, gradually, right? Gradually, I would attend more and more classes as my stamina, I guess, improved, but yeah. She would, but my mom would also have to stay at the school while I was there, just to make sure nothing went wrong.

Carolyn Bouldin: And Kelly was really stubborn. She knew her class would graduate in the year 2000, and that was the goal she had was to graduate in the year 2000. So the school board gave us a home-bound tutor to come by our house, who did the spring work of that first-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, did the fall.

Carolyn Bouldin: Or did the fall work. And because I’m a licensed teacher, I did the other semester. So we worked Saturdays, Sundays, and I don’t think Kelly remembered too much of what she learned, but her home-bound teacher could teach her something and test her that second, and she could make 100% on the test. She was a wonderful lady, and surprisingly I found in college, you wrote about some of those things that you learned-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, it was-

Carolyn Bouldin: : … that I didn’t think you remembered, but you did.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal : It’s in there, but-

Carolyn Bouldin: In there somewhere. Got this new computer that’s perfect, but you have to go into settings to get the-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: You see all these great Facebook things like, “It’s in the Bermuda Triangle,” or things like that, not being able to access what you need, which is pretty much the story of my life as far as words go. I’m always like, “What’s that? What do you call that?”

Q&A: The Accident that Caused my TBI

Carrie: Carolyn, can you take us back to that day? How did you find out about the accident? What were some of your initial experiences?

Carolyn Bouldin: Kelly was just 15, a couple of days after her birthday. And I was not popular, because I didn’t let her ride with teenage drivers. The first night I let her do that was after her first JV cheerleader game. I let her ride with an 18-year-old family friend, who had never had a beer, a few blocks from my home to get supper after she cheered at a game, and that was my first time I let her go out. It was about 10:00 at night, and she didn’t come home, and I got a call at 10:20 from, mercifully, the doctor whose yard the car crashed in.

There was a bend in the road and a distracted driver. He just hit the telephone pole, and I never cried. I went into the numb zone, so to speak. My husband and I went directly to the hospital. I had to endure a lot of red tape. And we were, after a while, taken in to say goodbye to Kelly, because they said she probably wouldn’t live. She was hemorrhaging in all ventricles of her brain. She just didn’t die. It was rough. I don’t know where I was, but I was on the outside looking in.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal : Yeah, I was not letting you get rid of me that easy.

Carolyn Bouldin: No. I didn’t feel hopeful. I didn’t feel anything. It just wasn’t my life. That’s the way I felt. It was impossible.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Through the looking glass.

Carolyn Bouldin: Yeah, I definitely think we walked through the looking glass. I didn’t think we’d ever be able to walk back, but we could now, but we don’t want to. We like the people over here on this side of the looking glass. And then, it was months before Kelly came home. We went from a month in the hospital here to inpatient therapy elsewhere where Kelly had to learn… And she was blind, and her right hand still doesn’t work very well, but relearning every basic skill, except she knew computers really well.

We didn’t discover that for a while. She could fly on the computer. My first piece of advice, I don’t know whether it’s yours, for anybody is assume nothing at all, just assume nothing. Don’t assume that your person knows that your shoes should match. Don’t assume that they know what Christmas is, but Kelly, you had high-level skills, and I was trying to fill in the low-level skills. And I could see that your short-term memory was increasing over time. The first time Kelly remembered something from one day to the next day was a landmark moment, because I could see you were improving by that.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal : But I mean, I can only imagine how hard it must have been, how frustrating. They had to tell me multiple times each day what had happened to me and where I was and why I was in the hospital.

Carolyn Bouldin: We didn’t mind. The doctors didn’t think Kelly would talk again, and I had to laugh, because I said, “Of all the skills that I know she will get back, it’s talking because she won’t be silent.”

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: I mean, I speak slow now, but that’s okay. I live in the South. People don’t really think twice about my speech.

Q&A: The importance of having a sense of humor with TBI

Carrie: There’s so many variables, and things are so different. We were talking before that when you were injured, there wasn’t even an internet. So Carolyn, you couldn’t even google traumatic brain injury.

Carolyn Bouldin: I had never heard of it, so it was difficult. I was lucky to have a sister who is a reference librarian at a university. And so, she was able to find materials for me, but it was hard. And I went to the school system, both locally, well, in North Carolina and in Washington DC, and generally found out all their materials on TBI were written from… They didn’t know any more than I did is what I’ll say. So I just started trying to find other memoirs.

I only found one, but bit by bit, I just started paying attention to Kel, because she was the only one who could really convey to me, once she started talking after about a month. She could convey to me what she needed, and I could see what was working and what wasn’t. So I just learned slowly, grateful to get the internet and cellphones, but I laughed a lot. I’m an English teacher, and strangely there’s a lot of humor involved, as Kelly woke from a coma. It’s not one day she’s asleep, and one day she’s awake. It’s a very slow awakening over months or years, and I think that was the hardest thing for me as a caretaker is I did not know what she didn’t know. She knew the Pythagorean Theorem, but she couldn’t multiply. And so, slowly, little by little, we filled in the gaps. I always said she was like a jigsaw puzzle, and we got the main portion in the middle, but the pieces of sky had to be put in by different people. And I’m still learning that you forget what a geranium might be or something simple-

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, you’ve got to keep a sense of humor. That’s imperative. If you’re going to survive a TBI, you just got to learn to laugh at yourself.

Carolyn Bouldin: I don’t know now everything Kelly doesn’t know or knows.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Yeah, but that’s true of anybody.

Carolyn Bouldin I’m 71 years old and I think her memory has surpassed mine at this point.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: And that is scary.

Q&A: How were you able to get published?

Carrie: Fantastic. Can you talk to us about how you were able to get published? Did you self-publish, or did you meet a publisher?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Well, actually, the act of finding a publisher to do my book, that actually took longer on this than writing the memoir. I mean, oh my goodness, I sent out myriad letters… letters, letters … query letters. And whenever someone would send the query back with a complaint, or not a complaint but for saying they weren’t interested, I would take the feedback they gave me, and I would rewrite the query letter. So the query letter had to be rewritten so many times, I would say at least 50 times, just to perfect it and, I queried well over 100 publishers before I found one, and that publisher ended up actually going out of business. And so, I had to start the whole process over again, but it was worth it. I mean, I don’t know. After reading my book, you can probably tell that I am not one to give up on things. And so, I had had a few chats with Victor Volkman of Loving Healing Press, and he was interested in my book, but he said that he already had too many books in the works to be published.

And so, he could not begin on my manuscript until the following fall, and so I was like, “Okay, well, I’ve already found someone. Thank you, anyways,” but when my initial publisher went bankrupt, I recontacted Victor and we were able to get started actually in the middle of the summer, because yeah, patience is not one of my strengths. I bugged him until he would finally get started with me, so we got it out. We got the book out in the fall in October.

It must be almost like having your child. That’s how people usually describe it. My friend just published a book and had a baby, and she’s like, “I had two babies in 2020.” You go through so much with it. It must almost feel like that. Can you dispel a couple myths? We work a lot with people who want to share their story, and there are sometimes people that think you’re going to write a book and be rich from it.

Carolyn Bouldin: Can I say something? I think you’re very blessed if you don’t have to spend money on it. Kelly’s never had to spend money on it.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: We got Moden History Press as an imprint of Loving Healing, and they have taken all the costs, and you’ve made money on it and made money on speeches, but I didn’t get rich. It’s not something you do to get rich. You get rich writing, if you can write bestsellers and more than one. After a long time, you can start actually making money from it, but really I just wanted to write my story to help other people in similar situations. I feel blessed that I was able to find two publishers who were willing to take on expenses so that I can have my voice heard.

Carrie: That’s wonderful. And Dr. Goldsmith, I think you addressed this a little bit, but he asks, “Any suggestions about where one can find a good editor for a nonfiction book about brain injury?” So that’s a great question. Did you work with an editor? Do you have any suggestions for someone?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: Well, my publisher provided us with an editor, but also my mother has edited several pieces for other people, and she went back and edited after the editor.

Carolyn Bouldin: I edited the editor.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: But there’s also the Publishers Marketplace, I believe, online. If you want to pay to subscribe to the Publishers Marketplace, they have editors that you can contact and reach out to. I’m sure they’re not free. That’s the only caveat there, but you can find editors that way, but I would just say if you do speak with a publisher or… Who did I go to? What is that person called that… See, I have trouble remembering names and stuff like that, but you send query letters, and first you want to find an agent.

Carolyn Bouldin: You didn’t have an agent.

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: A literary agent, that’s who I started querying first, and I did have several agents who were willing to work with me, but after seeing the amount of money they would take, they take a large cut from your profits from the book, from the publisher. And I was just like, “You know what? I don’t need this.” So I started contacting the publishers directly once I had my query letter perfected, but I’d say, first, you would want to go to a literary agent. And if you do get a literary agent, they will recommend editors to you.

And like I said, I’m not really sure of that whole process, who pays for what, but they will help you and they can guide you. And I would say normally most of the people that I queried, most of the literary agents as well as publishers, want to see the first 10 pages of your book and things like that, just to get an idea. That was a problem for me though, because the first 10 pages of Lost in My Mind aren’t even really my words. They’re my mother’s words that I transcribed, and I didn’t feel like that was a good depiction of the meat of my story. So I would tend to look for people who wanted to read the whole thing and then get back to me, then it just becomes a whole waiting game. And I won’t talk about that, but yeah. It was a very, very long, hard process.

Q&A: What was it like to write a book?

Carrie: Kelly, can you walk us through the process of writing a book, because we’ve worked with and talked with a lot of people who want to write a book? Did you dedicate a certain amount of time every day to writing? What was the process like for you?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: The process was very long and arduous, but basically I did not set aside certain times when I would sit down and write, mainly because of my son. Pretty much, I had to add and be on his schedule for feedings or when he would cry, I go to him and rock him. So basically, while I was at home with him, I just would write every time that I wasn’t in need from Alex. Alex is my son. Every time I was not with him or doing laundry or doing something else that housewives need to be in charge of, I would spend all of my time just writing my book and trying to go through all my mom’s notes and make sense of them, and make them into paragraphs and things like that.

And then, once I finished compiling all of her stuff together, I gave her that portion of the book, the first half, and let her read through it, because I did have to put in some additional sentences or some words to make the sentences make sense and go along with one another. So I wanted her to be able to give feedback on how everything sounded to her and what are add-in stuff, if I made something seem one way when it was actually another. And then, I started in on my portion of the book. That went a little bit quicker, since there wasn’t another person whom I had to check with.

Carrie: Kelly, can you walk us through the process of writing a book, because we’ve worked with and talked with a lot of people who want to write a book? Did you dedicate a certain amount of time every day to writing? What was the process like for you?

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal: The process was very long and arduous, but basically I did not set aside certain times when I would sit down and write, mainly because of my son. Pretty much, I had to add and be on his schedule for feedings or when he would cry, I go to him and rock him. So basically, while I was at home with him, I just would write every time that I wasn’t in need from Alex. Alex is my son. Every time I was not with him or doing laundry or doing something else that housewives need to be in charge of, I would spend all of my time just writing my book and trying to go through all my mom’s notes and make sense of them, and make them into paragraphs and things like that.

And then, once I finished compiling all of her stuff together, I gave her that portion of the book, the first half, and let her read through it, because I did have to put in some additional sentences or some words to make the sentences make sense and go along with one another. So I wanted her to be able to give feedback on how everything sounded to her and what are add-in stuff, if I made something seem one way when it was actually another. And then, I started in on my portion of the book. That went a little bit quicker, since there wasn’t another person whom I had to check with.

Watch the entire Q&A session as recorded on Zoom

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal speaks about recovery from Traumatic Brain Injury

Kelly Bouldin-Darmofal recorded live with the Brain Injury Alliance of Arizona (BIAA).

Kelly Bouldin Darmofal survived a grievous car accident at age 15 that left her in a coma for months. Her struggle back to a normal life has been an inspiration to other TBI survivors. Her interests include educating teachers about how to help students with TBI learn better.